Answered By: Victoria Peters Last Updated: Dec 19, 2022 Views: 668

Imagine if all creators had to wait for a copyrighted work to be in the public domain before they used that work? Or if scholars always had to seek permission to use or quote, and that permission could be denied with no recourse? Happily, copyright law gives us the flexibility to allow some uses that are made during the copyright term without permission. One of the most famous of all the copyright limitations in the Copyright Act does just that: the fair use exception.

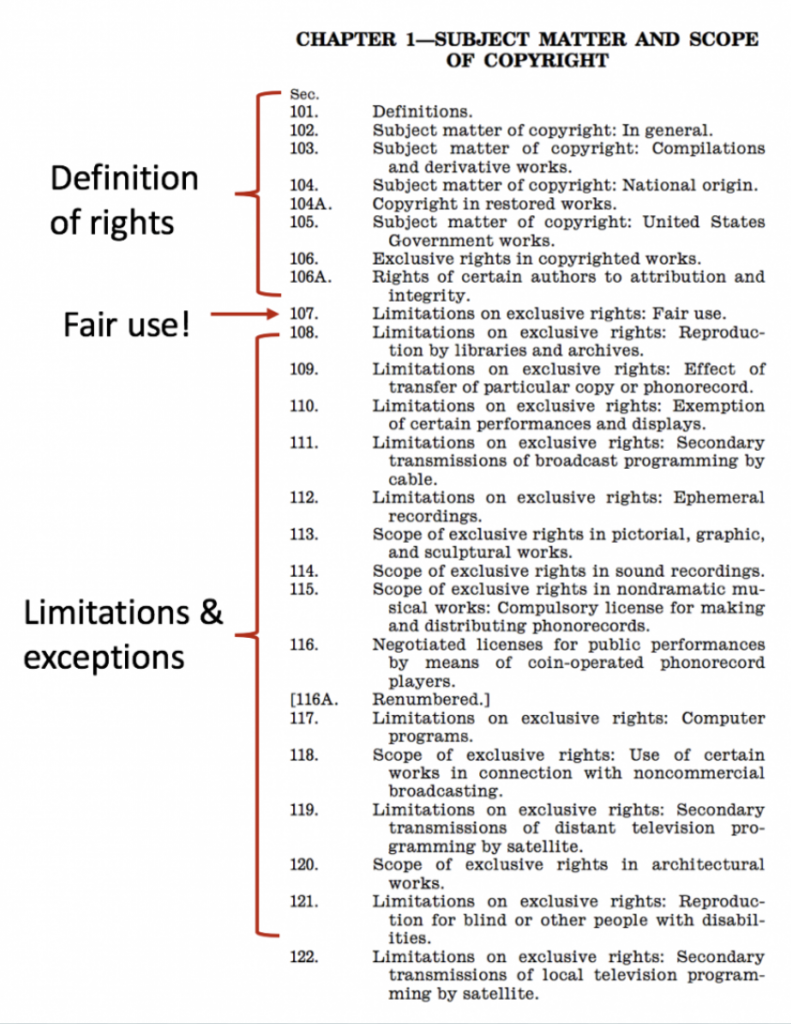

Under fair use, a person may use certain amounts of copyrighted material without permission from the copyright owner in some circumstances. The doctrine itself was rooted in both English and U.S. case law, but was eventually codified in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act. Fair use, as you can see in the image below, sits in the middle of the organized balance in the Copyright Act; it is squeezed right between the exclusive rights and more specific exceptions.

Fair use is a user’s right that allows individuals to exercise one or more of the exclusive bundle of rights of the copyright owner, without obtaining the permission from that copyright owner, and without the payment of any license fee.

To decide whether a use is fair, courts must consider at least four factors that are specifically mentioned in the Copyright Act.

17 U.S.C. §107

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.

In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The first factor is the purpose and character of the use. Here courts ask whether the material has been transformed by adding new meaning or expression, or whether value was added by creating new information, meaning, or understanding. When a work is used for a different purpose than the original, the factor will likely weigh in favor of fair use. If it simply acts as a substitute for the original work, the less likely it is to be fair. Courts may also look at whether the use of the material was for commercial or noncommercial purposes under this factor, but this is rarely a determinative consideration.

The second factor looks at the nature of the copyrighted work. Here courts look at whether the copyrighted work that was used is creative or factual in nature (a song or a novel vs. technical article or news item). The more factual the work, the more likely this factor will weigh in favor of fair use. On the flip side, the more creative the copyrighted work, the more likely this factor is to weigh against fair use. Courts may also consider whether the copyrighted work is published or unpublished. If the work is unpublished, this factor is less likely to weigh in favor or fair use. Note that this factor has been slightly deemphasized by the courts over the last twenty years.

The third factor is the amount and substantiality of the portion taken. Under this factor, courts look at how much of the work was taken, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitatively, courts look at how much of the original work was used (e.g., all the pages, the entire work of art). Qualitatively, some courts look at whether the “heart” of the work was taken (e.g., the essential bit of the work that is why people want to engage and acquire the work). The more that is taken, quantitatively and qualitatively, the less likely the use is to be fair. That said, copying a full work can absolutely be a fair use depending on the circumstances.

Finally, the fourth factor is the effect of the use on the potential market. The essential question courts ask here is whether this use will undermine the market, or the potential market, for the work that was copied. In assessing this factor, courts consider whether the use would hurt the market for the original work (for example, by displacing sales of the original).

Transformative fair use

In 1841, the U.S. decided its first fair use case. And, as case law developed, so did new and different fair use theories. One of the more interesting developments in fair use litigation was the emergence of transformative fair use. Use of any copyrighted materials is substantially more likely to pass fair use muster if the use is transformative. A work is transformative if, in the words of the Supreme Court, it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.” Transformative fair use is still a use without permission, but it is the legal engine which drives scholarship, research, and teaching.

The last two decades has seen a shift in courts analysis of the fair use test in creative endeavors like these. In transformative fair use, we see the courts collapsing the traditional “four fair use factors” to ask the following questions:

- Does the new use transform the material, by using it for a different purpose?

- Was the amount taken appropriate to the new, transformative purpose?

And, importantly, it helps to identify that this new transformative use has a different purpose than the original item’s purpose. For example, the original purpose of the fictional books in the Copyright Use Case was for entertainment. The new use should be for a different purpose—and arguably, the new purpose would be to add commentary or analysis that reveals a new meaning or message, altering the original works with new commentary, expression, meaning, or message.

Fair use law is well equipped to be adaptable to various scenarios. That’s the purpose of fair use: flexibility. Fair use is not mechanically applied or even weighed equally. Courts take into account all the facts and circumstances of a specific case to decide if use of copyrighted material is fair. And scholars, librarians, lawyers, students, staff, and faculty can also use the fair use statute and legal decisions to evaluate their own fair use risk calculus for their own scenarios.

Was this helpful? 0 0